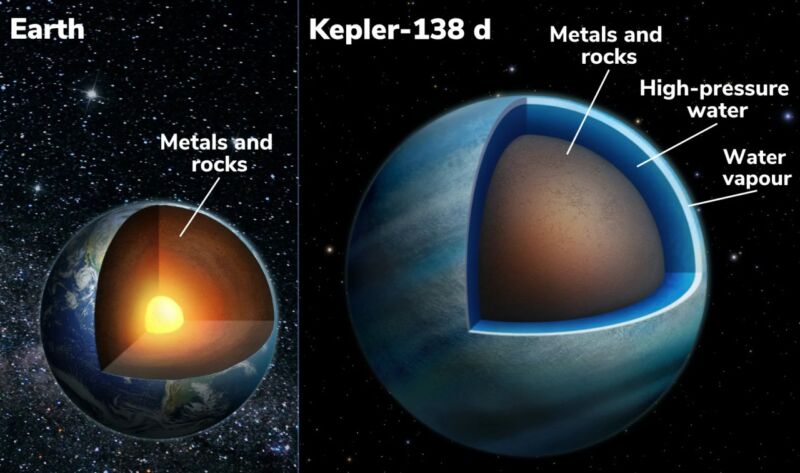

The possibility that there is liquid water on an exoplanet’s surface usually flags it as “potentially habitable,” but the reality is that too much water might prevent life from taking hold.

“On Earth, the ocean is in contact with some rock. If we have too much water, it creates high-pressure ice underneath the ocean, which separates it from the planet’s rocky interior,” said Caroline Dorn, a geophysicist at ETH Zurich, Switzerland, who led new research in exoplanet interiors.

This high-pressure ice prevents minerals and chemical compounds from being exchanged between the rocks and the water. In theory, that should make the ocean barren and lifeless. But Dorn’s team argues that even exoplanets that have enough water to form such high-pressure ice can host life if the majority of the water is not stored in the surface oceans but is held much deeper in the planet’s core. The water in the core can’t sustain life—it’s not even in its molecular form there. But it means that a substantial fraction of a planet’s water isn’t on the surface, which makes the surface oceans a little more shallow and prevents high-pressure ice from forming at their bottom.

Planetary youngsters

“If you looked at the exoplanet community three to five years ago, everybody was thinking that [water] can only be present on the surface of planets,” Dorn said. Scientists, having no evidence to the contrary, simply assumed alien worlds were built how they thought the Earth was built, with the water primarily present in the surface oceans, with some portion, around 40 million cubic kilometers, held deeper in the crust. But all this reasoning went out the window in 2020 when a team of scientists at the University College London published a study claiming the Earth was not built that way at all.

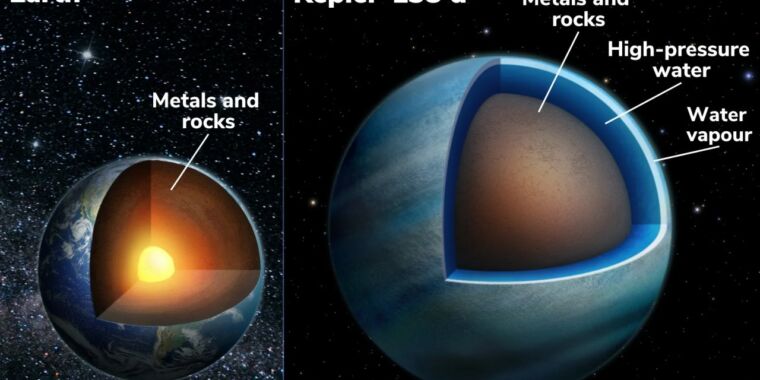

Instead, the 2020 study argued that the majority of water on Earth is not in the oceans or the crust but in the core of the planet and that the core can host 30 to 37 times as much water as all our surface oceans combined. “When the planet is very young and hot, you have a soup of magma with everything mixed in—you have silicates contained in the mantle of the planet but also drops of iron that will eventually sink down and form the core,” Dorn said.

Part of the water present in this magma soup associates with the silicates and can one day end up in the surface oceans. Another part stays with iron and sinks down to the core with it. At the immense temperatures and pressures found in the nascent worlds, iron can bind roughly 70 times more water than silicates.

As a rule of thumb, if a planet is heavier, a large portion of its water will go down to the core and stay there. And this may be a good thing for our hopes of finding life in space.

Giving life a chance

Even with immense precision of modern instruments, James Webb Telescope included, the only way we can guesstimate the water budget of an exoplanet is through indirect cues: a bulk density calculated from the best estimations of its mass and radius.

Before Dorn’s study, whenever we came across an exoplanet with exceptionally high water budget, we assumed the water was in its surface oceans, meaning the oceans were super deep and had absurdly high pressures at their bottom. That was because the hard data we have only tells us what portion of the planet is made of water—it says nothing about its distribution.

“Because now we think the water can also be stored in the core, we can have ten times more water on the planet before we reach these high pressures. It’s an order of magnitude difference,” Dorn said. Since the majority of water goes down to the core with the iron, only a small portion remains near the surface to form oceans as we know them, reducing the pressures on the ocean floors.

This means the pool of potentially habitable worlds has grown significantly wider. Still, finding conclusive evidence of life on one of these planets remains a huge challenge.