January 23, 2025

5 min read

My Climate Protest Arrest Shows the Problem with ‘Social Tipping Point’ Theory

People hoping that progress on climate action will accelerate like sudden changes in our physical world must prepare for a long, hard struggle

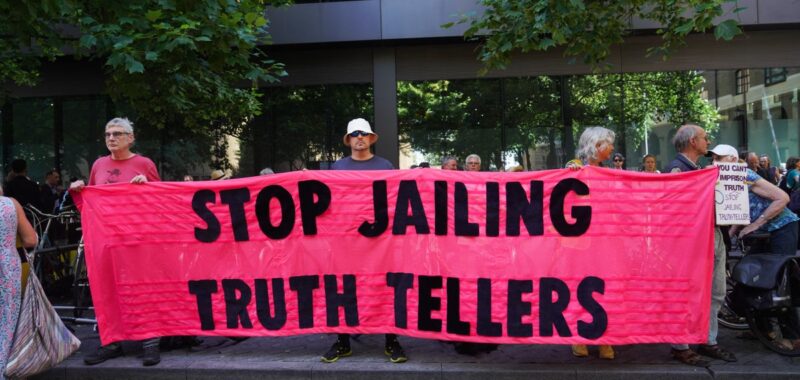

Supporters outside Southwark Crown Court, London, United Kingdom, where five Just Stop Oil activists were sentenced to 5 and 4 years in prison for conspiracy to causepublic nuisance on the 18th of July 2024.

Kristian Buus/In Pictures via Getty Images

Eyeing the bruises on the knuckles of the police officer arresting me, I took a deep breath and explained why we need to act faster to avoid climate catastrophe. Standing on a traffic island in London, I looked straight into his body-worn video camera, and hoped the speech would make it to the courtroom.

On a cold November afternoon in 2023, I was protesting with the nonviolent civil resistance group, Just Stop Oil (JSO), to call for action to prevent what U.N. secretary-general António Gutierres has called “global boiling.” One reason was a study from British Antarctic Survey researchers that had just been published. It found that we’ve lost control of melting of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet, which contains enough ice to raise sea levels by five meters. At least one glacier there has passed a “tipping point,” scientists have found, where its melting is rapid and irreversible.

Tipping points in our physical world weren’t my only motivation. By risking arrest as a law-abiding science journalist, I hoped to push society past a social tipping point to speed up climate action. In doing so I am a living experiment, because researchers are unsure what it takes to cause social changes to also become rapid and irreversible.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

In July, the left-wing Labour Party won the U.K. government and committed to not granting new fossil fuel exploration licences, as we had called for in our protests. Yet my experiences—and journalism—make me less confident that we’ve reached a “social tipping point” on climate action. Rather than give up in despair, however, I believe this means we must be more resolute. The only way to reduce the severity of the climate catastrophe we face is to keep pushing, even if we never reach a tipping point.

Social tipping points are embedded in the key principles of Just Stop Oil’s fellow activist group Extinction Rebellion (XR), with whom I also protest. The group hopes to mobilise 3.5 percent of the population, meaning over two million people in the U.K., a figure originating from political scientists Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan. Comparing 323 campaigns conducted from 1900 to 2006, they found nonviolent protests like JSO and XR’s were more than twice as effective as violent ones. When Chenoweth later analysed that data for a 2013 TedX talk, she found that nonviolent campaigns that involved more than 3.5 percent of the population led to long-lasting political change.

Such social tipping point theories featured in one of four sections in the Global Tipping Points Report 2023 report produced by 200 climate researchers from 25 institutions worldwide. One section’s author, Viktoria Spaiser, from the University of Leeds, says that, in fact, there’s no magic number that will definitely flip a social tipping point. Each society will differ, Spaiser told me, according to the forces reinforcing or opposing changes.

The day of my protest illustrated opposing forces in play in the U.K. It was November 11, Veterans Day, known as Remembrance Day in my country. The police officer arresting me said he had come from fighting right-wing English Defence League thugs near the Cenotaph, London’s main war memorial. He was unimpressed by my speech. As I waited, handcuffed, to be thrown into a police cell, he told me that he just wanted to go home. The right-wing protests and the lack of governance shown by the exhaustion and underresourcing of the police felt typical of a world where climate action is lacking.

Manjana Milkoreit from the University of Oslo led the Global Tipping Points Report’s section on governing physical tipping points in global climate change. Though she’s a political scientist, she focuses on responses to physical tipping points, because she’s uncertain that social ones even exist.

Milkoreit cautions against overreliance on social tipping points to drive change. The looming catastrophe of physical tipping points led us to invent social ones “out of a psychological need for speed in our solutions,” she says. They also give politicians and other decision-makers a “cop out,” she worries. “They say ‘Oh, yes, I know, we have no more time, but we’ll get there with a social tipping point.’ It’s another excuse to not do the hard work of decarbonizing now.”

Following my arrest, I represented myself at trial in June 2024, just a month before the new U.K. government delivered the halt to fossil fuel licensing we had sought. The judge found me not guilty of willful obstruction of the highway. Despite my good fortune, many other JSO protestors have been imprisoned, reducing our capacity for further protest. This again shows the opposing forces in play, and my fellow protestors’ words suggest we’re far from tipping society into adequate climate action: recently JSO’s Roger Hallam and Daniel Shaw, wrote from their cells to encourage others to “carry on regardless” even as “people seem more willing than ever to stick their heads in the sand.”

At a broader political level, the Global Tipping Points Report describes five potential negative social tipping processes. These include the breakdown of social norms and ties, radicalization and polarization, conflict, financial destabilization and displacement of people. Spaiser says that if policies trying to trigger social tipping points, like subsidies and incentives for solar power generation have arguably achieved, are unsuccessful, then countries shouldn’t withdraw them. That may only trigger the negative tipping processes. Instead, they should keep driving slow change. “We’re at such a critical state that if we don’t do anything, the system will just slide into negative social tipping points,” Spaiser says.

Protestors likewise need to continue even if they don’t trigger positive tipping points. I recognize now that I wanted to test the social tipping point theory to appease my own “psychological need for speed,” as Milkoreit calls it. Today my need for speed is being frustrated. Clear forces oppose necessary changes, particularly record profits for oil companies that have led them to renege on plans to transition to clean energy.

As such, I agree with Hallam and Shaw’s assessment of the difficult place climate action is in. Facing such a reality, it might be tempting just to give up in the face of opposing forces, but we must not. We are currently on track for 2.7 degrees Celsius of warming beyond what global temperatures were before the industrial revolution. At the 1.5 degrees C threshold we’re currently at, across the world, droughts will last two months on average. At 2 degrees C, they will last four months. At 3 degrees C, they will last 10 months. When it comes to climate action, it’s not as simple as winning or losing. As many of us as possible must push against the opposition, as any fraction of a degree that we reduce future temperatures by, matters to humanity.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.